System Failure: 7 Shocking Causes and How to Prevent Them

Ever felt the ground drop beneath you when a critical system suddenly crashes? That heart-sinking moment when everything stops—power, data, communication—is what we call a system failure. It’s not just inconvenient; it can be catastrophic.

What Is a System Failure?

A system failure occurs when a complex network of components—be it technological, organizational, or biological—ceases to function as intended. This breakdown can range from a minor glitch to a total collapse, affecting everything from your smartphone to global financial markets. According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), system failures cost U.S. businesses over $70 billion annually in downtime and recovery efforts alone (NIST).

Defining System and Subsystem

At its core, a system is any interconnected set of elements working toward a common goal. Think of a car: the engine, transmission, brakes, and electronics all form a system. When one part fails—like a blown alternator—it can trigger a cascade that disables the entire vehicle. Subsystems are smaller functional units within the larger system. A failure in one subsystem doesn’t always mean total system collapse, but it often compromises overall performance.

- A system can be mechanical, digital, biological, or social.

- Subsystems operate semi-independently but rely on integration.

- Redundancy in subsystems can mitigate failure risks.

Types of System Failure

Not all system failures are created equal. They vary by cause, scope, and impact. Common types include:

Hardware failure: Physical components like servers, circuits, or engines break down.Software failure: Bugs, crashes, or incompatibilities disrupt digital operations.Human error: Mistakes in operation, design, or maintenance lead to breakdowns.Environmental failure: Natural disasters or extreme conditions overwhelm system resilience.Cascading failure: One failure triggers a chain reaction across interconnected systems.”A system is only as strong as its weakest link.” — Donald Norman, cognitive scientist and design expertCommon Causes of System FailureUnderstanding why system failures happen is the first step toward preventing them.While some causes are unpredictable, many stem from avoidable oversights in design, maintenance, or human behavior.

.Research from MIT’s Engineering Systems Division shows that over 60% of major system failures are rooted in poor communication and flawed decision-making processes..

Poor Design and Engineering Flaws

Even the most advanced systems can fail if their foundational design is flawed. The 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger disaster is a tragic example. Engineers had warned about O-ring failures in cold weather, but design assumptions overruled safety concerns. When the shuttle launched in freezing temperatures, the O-rings failed, leading to an explosion that killed seven astronauts.

Design flaws often go unnoticed until stress tests or real-world use expose them. In software, this might mean inadequate load testing. In infrastructure, it could mean underestimating environmental stressors like wind, heat, or corrosion.

- Lack of stress testing during development.

- Over-optimization for efficiency at the expense of resilience.

- Inadequate consideration of edge cases or extreme conditions.

Insufficient Maintenance and Monitoring

Systems degrade over time. Without regular maintenance, wear and tear accumulate until failure becomes inevitable. The 2003 Northeast Blackout, which affected 50 million people across the U.S. and Canada, was caused by a software bug in an alarm system and untrimmed trees contacting power lines—both preventable with proper monitoring.

Modern predictive maintenance tools use sensors and AI to detect anomalies before they escalate. However, many organizations still rely on reactive maintenance, fixing problems only after they occur.

- Delayed or skipped maintenance schedules.

- Lack of real-time monitoring systems.

- Failure to act on early warning signs.

System Failure in Technology and IT Infrastructure

In the digital age, system failure often means IT infrastructure collapse. From cloud servers to local networks, technology underpins nearly every aspect of modern life. When these systems fail, the consequences can be immediate and far-reaching.

Server and Network Outages

Server outages are among the most common forms of system failure in IT. In 2021, Facebook (now Meta) experienced a global outage lasting nearly six hours due to a misconfigured Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) update. The error made Facebook’s domains unreachable, disrupting Instagram, WhatsApp, and internal communications.

Network outages can stem from hardware failure, software bugs, or cyberattacks. Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, for instance, flood networks with traffic until they collapse. According to Cloudflare, DDoS attacks increased by 75% between 2020 and 2022.

- BGP misconfigurations can disconnect entire networks.

- Hardware redundancy (e.g., backup servers) reduces downtime.

- DDoS mitigation services are essential for high-traffic platforms.

Data Corruption and Loss

Data is the lifeblood of modern organizations. When data becomes corrupted or lost, system failure follows. This can happen due to software bugs, storage device failure, or human error. In 2017, a simple typo during a routine maintenance task caused Amazon Web Services (AWS) to delete critical files, disrupting thousands of websites and apps.

Regular backups, checksum verification, and version control are essential safeguards. The 3-2-1 backup rule—three copies of data, on two different media, with one offsite—is a gold standard in data resilience.

- Use RAID configurations to protect against disk failure.

- Implement automated backup schedules.

- Test data recovery procedures regularly.

“The only thing worse than a system failure is a system failure you didn’t prepare for.” — Linus Torvalds, creator of Linux

System Failure in Critical Infrastructure

Critical infrastructure—power grids, water supplies, transportation networks—relies on complex systems that must operate continuously. When these systems fail, public safety and economic stability are at risk. The U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) classifies 16 sectors as critical, all vulnerable to system failure.

Power Grid Collapse

Power grid failures can cascade across regions. The 2003 Northeast Blackout started with a single transmission line in Ohio but quickly spread due to inadequate monitoring and communication. Within minutes, eight U.S. states and parts of Canada were without power.

Modern smart grids use sensors and automation to detect and isolate faults, but legacy systems still dominate in many areas. Investment in grid modernization is critical to prevent future failures.

- Aging infrastructure increases failure risk.

- Smart grid technology improves fault detection.

- Decentralized energy sources (e.g., solar microgrids) enhance resilience.

Water Supply and Treatment Failures

When water treatment systems fail, public health is on the line. In 2021, a cyberattack on a Florida water treatment plant allowed hackers to increase sodium hydroxide levels to dangerous levels. Fortunately, an operator noticed the change in time.

Water systems are increasingly connected, making them vulnerable to both cyber and physical threats. Regular security audits and manual override capabilities are essential.

- Cybersecurity must be integrated into water infrastructure.

- Chemical monitoring systems need real-time alerts.

- Staff training is crucial for detecting anomalies.

Human Factors in System Failure

Despite advances in automation, humans remain a central factor in system performance—and failure. The Swiss Cheese Model, developed by James Reason, illustrates how multiple layers of defense can fail simultaneously due to human error, procedural gaps, and organizational weaknesses.

Cognitive Overload and Decision Fatigue

Operators managing complex systems often face overwhelming amounts of data. Cognitive overload occurs when the brain cannot process all incoming information, leading to missed warnings or poor decisions. In aviation, this contributed to the 2009 Air France Flight 447 crash, where pilots misinterpreted instrument readings during turbulence.

Designing intuitive interfaces and automating routine tasks can reduce cognitive load. Decision fatigue—making poorer choices after prolonged mental effort—also plays a role in shift-based operations.

- Human-machine interfaces should prioritize clarity.

- Automation should support, not replace, human judgment.

- Shift schedules must account for mental fatigue.

Organizational Culture and Communication Breakdown

A toxic or hierarchical workplace culture can suppress vital information. At NASA before the Columbia disaster in 2003, engineers raised concerns about foam strike damage, but their warnings were dismissed due to organizational pressure to maintain launch schedules.

Open communication, psychological safety, and cross-functional collaboration are key to preventing failure. Google’s Project Aristotle found that psychological safety—the belief that one won’t be punished for speaking up—is the top factor in team effectiveness.

- Encourage reporting of near-misses without fear of blame.

- Implement anonymous feedback channels.

- Foster a culture of continuous learning.

Cascading Failures and Systemic Collapse

One of the most dangerous aspects of system failure is its potential to cascade. A small failure in one area can trigger a chain reaction across interdependent systems. This is especially true in tightly coupled networks where components react quickly to changes in others.

The Domino Effect in Interconnected Systems

The 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster began with an earthquake and tsunami—natural triggers—but the real failure was systemic. Backup generators flooded, cooling systems failed, and multiple reactors melted down. The interconnectedness of power, cooling, and safety systems meant one failure amplified the next.

In finance, the 2008 global crisis was a cascading failure. Subprime mortgage defaults triggered credit market collapses, bank failures, and global recession. No single entity caused it; the system itself was fragile.

- Interdependence increases efficiency but reduces resilience.

- Fail-safes must be isolated from primary systems.

- Stress-testing for multiple failure points is essential.

Black Swan Events and Unpredictable Triggers

Coined by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, a “Black Swan” event is rare, unpredictable, and has extreme impact. The COVID-19 pandemic was a Black Swan for global supply chains. Factory shutdowns, shipping delays, and demand spikes caused system failures across industries—from healthcare to retail.

While such events can’t be predicted, systems can be designed to be antifragile—gaining strength from stress. Diversified supply chains, flexible operations, and scenario planning help organizations adapt.

- Antifragility is better than mere resilience.

- Scenario planning prepares for low-probability, high-impact events.

- Diversification reduces dependency on single points of failure.

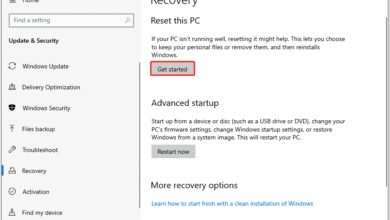

Preventing and Mitigating System Failure

While no system can be 100% failure-proof, robust strategies can drastically reduce risk. Prevention requires a combination of technology, process, and culture. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security recommends a “defense in depth” approach—layered safeguards that protect even if one layer fails.

Redundancy and Fail-Safe Mechanisms

Redundancy means having backup components ready to take over if the primary one fails. Aircraft, for example, have multiple hydraulic systems. If one fails, others maintain control. Similarly, data centers use redundant power supplies and network connections.

Fail-safe mechanisms ensure that when a system fails, it defaults to a safe state. Elevators stop automatically if cables break. Nuclear reactors have control rods that drop by gravity during power loss.

- Redundant systems should be physically and logically isolated.

- Fail-safes must be tested under real failure conditions.

- Over-reliance on redundancy can create false confidence.

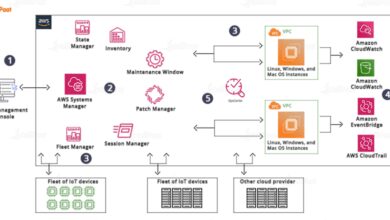

Continuous Monitoring and Predictive Analytics

Modern systems generate vast amounts of data. When analyzed in real time, this data can predict failures before they happen. Predictive maintenance in manufacturing uses vibration sensors and machine learning to detect bearing wear in motors.

Tools like Splunk, Datadog, and Prometheus enable real-time monitoring of IT systems. Alerts are triggered when metrics deviate from normal patterns, allowing proactive intervention.

- Implement real-time dashboards for system health.

- Use AI to detect anomalies in large datasets.

- Set thresholds based on historical performance, not guesswork.

“The best way to predict the future is to design it.” — Buckminster Fuller, architect and systems theorist

Case Studies of Major System Failures

History is filled with lessons from system failures. By studying these cases, we can identify patterns, improve designs, and prevent future disasters. Each case reveals how a combination of technical, human, and organizational factors can converge into catastrophe.

The Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster (1986)

The Chernobyl disaster remains the worst nuclear accident in history. During a safety test, operators disabled critical safety systems, violating protocols. A power surge caused an explosion, releasing massive radiation.

The RBMK reactor design had a positive void coefficient—meaning reactivity increased if coolant boiled. This flaw, combined with poor training and a culture of secrecy, led to disaster. The failure was not just technical but systemic.

- Design flaws made the reactor unstable at low power.

- Operators lacked full understanding of reactor dynamics.

- Suppression of dissenting opinions prevented corrective action.

The Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill (2010)

The Deepwater Horizon explosion killed 11 workers and spilled 4 million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. Investigations revealed multiple system failures: a faulty cement job, a defective blowout preventer, and ignored pressure tests.

BP, Halliburton, and Transocean all shared responsibility. Cost-cutting decisions and poor risk assessment created a perfect storm. The blowout preventer, a last-line safety device, failed to activate due to a dead battery and design flaws.

- Safety systems were not independently tested.

- Pressure to complete the well led to skipped procedures.

- Regulatory oversight was inadequate.

What is a system failure?

A system failure occurs when a network of interconnected components stops functioning as intended, leading to partial or total breakdown. This can happen in technology, infrastructure, organizations, or biological systems.

What are the most common causes of system failure?

The most common causes include poor design, lack of maintenance, human error, cyberattacks, environmental factors, and cascading failures due to interdependence.

How can system failures be prevented?

Prevention strategies include redundancy, continuous monitoring, predictive analytics, robust training, open communication cultures, and regular stress-testing of systems.

What is a cascading failure?

A cascading failure is a sequence of failures in a system where the initial failure triggers subsequent breakdowns in interconnected components, often leading to widespread collapse.

Can AI prevent system failures?

Yes, AI can help prevent system failures by analyzing vast amounts of operational data to detect anomalies, predict equipment wear, and recommend maintenance before breakdowns occur. However, AI itself must be properly designed and monitored to avoid becoming a failure point.

System failure is not just a technical issue—it’s a multidimensional challenge involving design, human behavior, and organizational culture. From IT outages to nuclear disasters, the root causes are often a mix of flawed engineering, poor communication, and inadequate preparation. Yet, by applying lessons from past failures, investing in redundancy, and embracing predictive technologies, we can build systems that are not only resilient but antifragile. The goal isn’t to eliminate all risk—impossible in complex systems—but to manage it wisely. As we grow more dependent on interconnected networks, understanding and preventing system failure isn’t just smart engineering; it’s a necessity for survival.

Further Reading: